It says all you need to know about its ineffective climate policies.

by Jeff Conant, Friends of the Earth and Moira Birss, Amazon Watch

After years of pressure from shareholders and legislators, BlackRock finally seemed ready to acknowledge the climate crisis in January, when it announced it would “place climate at the center of its investment strategy.” On the surface, the move seemed to send a clear message that business as usual was over. Yet, it has been far from clear what practical good BlackRock’s commitment to a “climate-centered” investment strategy does for the climate — or the future of life on earth.

The 2020 shareholder season came and went with the world’s largest asset manager mostly giving a pass to some of the biggest climate destroyers on the planet. The big coal divestment BlackRock touted as the centerpiece of its new strategy? Turns out it lets 80% of the coal industry continue on unchanged. And despite its big talk, BlackRock remains the world’s largest investor in fossil fuels. It also continues to rake in huge profits from that other driver of climate catastrophe: agribusiness-fueled deforestation.

BlackRock is among the top three shareholders in 25 of the world’s largest publicly listed soy, beef, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, and timber companies, including several that have been linked to last year’s devastating fires in Brazil and Indonesia. Its holdings in these sectors are only increasing — by more than half a billion dollars since 2014. BlackRock also holds more than a 700 billion dollars in shares and bond holdings in members of the Consumer Goods Forum, a consortium of the world’s 400+ top consumer brands, which broadly failed to meet their commitments to end deforestation in their supply chains by 2020. In fact, since that commitment a decade ago, global tree cover loss has increased by 43 percent.

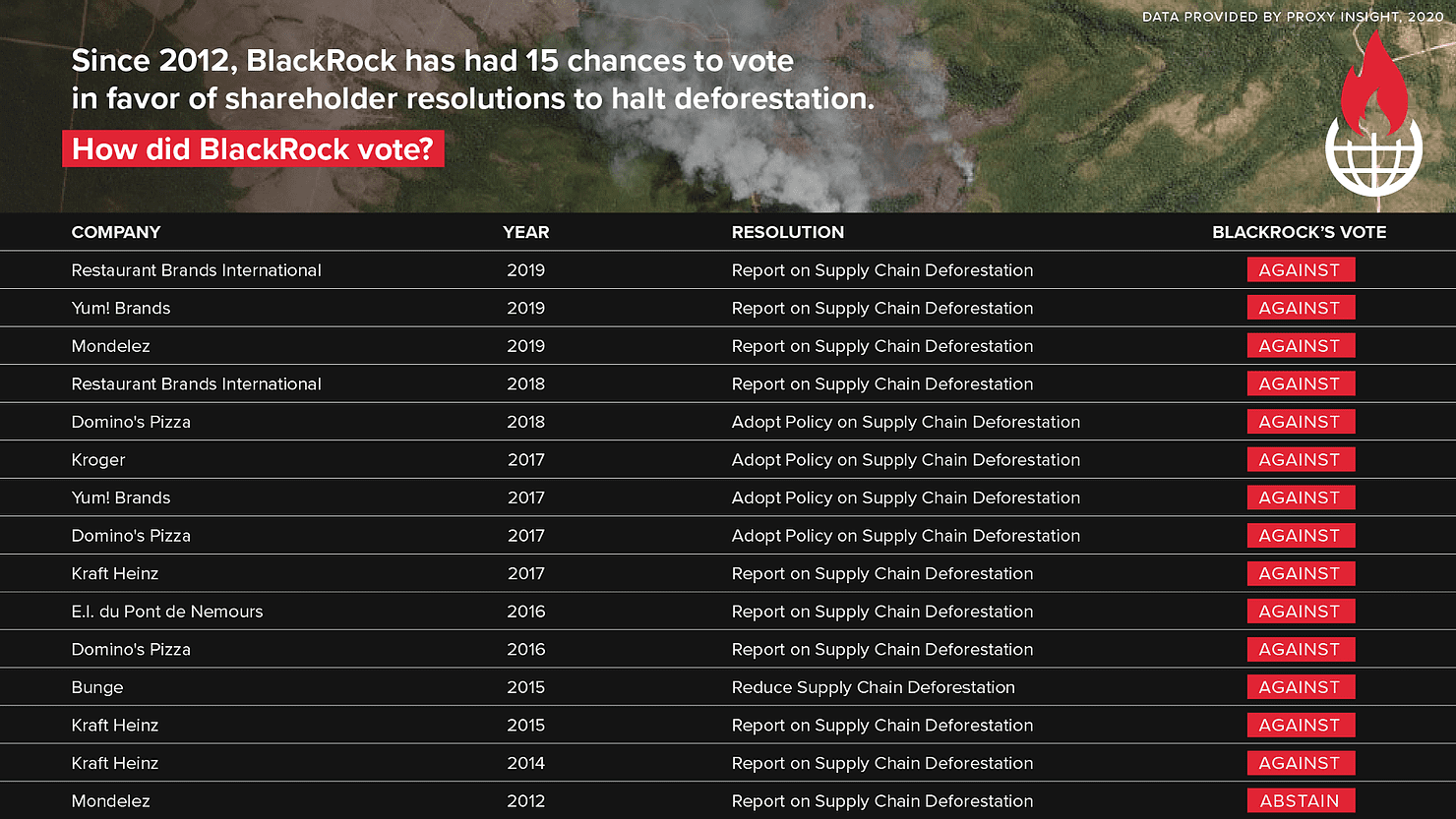

Since 2012, BlackRock has had 15 chances to vote in favor of shareholder resolutions to halt deforestation. One hundred percent of the time, it voted against action on deforestation.

If BlackRock is to make any credible claim that it has climate at the center of its strategy, it needs to begin unraveling its reliance on the destruction of rainforests — not next year, not in six months. Now.

Fire days are here again

In Brazil last year, fires set by illegal loggers and ranchers were the worst in a decade. The fires were intentional, blazing the path for soy and cattle production to expand deeper into the Amazon and the Cerrado, the country’s second most biodiverse biome. The Amazon fires sparked international outrage at the agribusiness interests behind the fires, including from some of BlackRock’s peers.

Indonesia, too, lost over two million acres of rainforest to fires last year at the hands of agribusiness, mostly due to expanding palm oil and paper pulp plantations. One report tallied that 900,000 people across Indonesia suffered respiratory problems from the smoke. All told, nearly 10,000 square miles of tropical rainforests were destroyed in the Amazon and Indonesia last year.

At the time of this writing, all signs point to a fire season in the Amazon and Indonesia that may be even deadlier than last year’s. But so far, BlackRock has done nothing of substance on the issue.

It’s not as if Larry Fink doesn’t know. Huge public protests at BlackRock offices from London to San Francisco saw to that. Following its January announcement on climate, BlackRock released a statement on its engagement with the companies responsible for destroying the world’s last standing forests and the attendant biodiversity crisis and violence against local, often indigenous, communities. In lieu of overt action to demand operational improvements by companies across the agribusiness sector, that engagement appears to consist of cordial dialogue with the management of a limited number agribusiness multi-nationals to “understand how management is incorporating sustainable agricultural practices into the business.”

BlackRock can exert a lot more influence than cordial appeals to encourage better disclosure practices, however. For instance, like all asset managers, BlackRock has at its disposal the ability to vote its shares at company shareholder meetings. As the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock has a lot of shares to vote. It just doesn’t.

BlackRock’s dismal record on climate voting is no secret — so we took a look at the firm’s votes on deforestation. Since 2012, BlackRock has had 15 chances to vote in favor of shareholder resolutions to halt deforestation. One hundred percent of the time, it voted against action on deforestation.

What concrete action actually looks like

BlackRock’s link to deforestation isn’t limited to palm oil-infused snack foods and cosmetics, however. The firm’s massive fossil fuel holdings also include $2.5 billion in crude oil companies drilling in the Western Amazon in areas directly overlapping the ancestral territory of indigenous peoples who have opposed the drilling through protest, lawsuits, and years of appeals to lawmakers.

With the threat of a deadlier fire season looming and enforcement of deforestation laws effectively curtailed in some countries by the COVID-19 pandemic, BlackRock needs to go well beyond open-ended engagement with forest destroying companies. To begin, it needs to articulate clear standards it will use to gauge companies’ approaches to the problem, as well as the consequences for companies that drive deforestation and its harms to people and biodiversity.

The best way to protect the world’s tropical forests is to recognize and respect the legal and customary rights and self-determination of the communities who live in and care for them.

That’s why we’ve put together a set of baseline principles that BlackRock (and all asset managers) should adhere to and adopt into a company policy. The principles we outline are largely distilled from existing international covenants like the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights — which is to say, all we’re asking is that BlackRock comply with existing norms for responsible business conduct.

The key takeaway from these principles is that the best way to protect the world’s tropical forests is to recognize and respect the legal and customary rights and self-determination of the communities who live in and care for them. This requires, at minimum, compliance with the internationally recognized right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), consultation on policies and operations that affect indigenous peoples and local communities, and accountability for rights violations. Yet not a single large asset management firm has an explicit policy or a publicly available set of guidelines on the issue.

So, today we call on BlackRock to recognize the need to adopt this set of Principles on Forests, Land, and the Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.